► First details of Ferrari’s EV revealed

► It won’t be a supercar…

► …but it’ll be brimming with tech

There is nowhere to hide. Ferrari is synonymous with magnificent combustion engines; fuel-burning works of art from glorious bloodlines that stretch back decades – back, in fact, to the middle of the last century, when the first Ferrari V12 roared through Maranello’s iconic gates.

That massive weight of history helps Ferrari sell new V6s, V8s and V12s. But it surely threatens to crush this, the first Ferrari electric car, like a satsuma in a steel press, the car’s absence of music, of heritage and of red-crinkle cam covers damning it to failure before it even turns a wheel. Indeed, almost more than with any other car company, the idea of an electric Ferrari feels intrinsically oxymoronic.

What’s more, it’s not like Ferrari can check its electric car homework against anyone else’s. Yes, newcomers like Rimac and born-again Lotus have blazed a (commercially unsuccessful) all-electric performance trail. But an EV from Lamborghini or Aston Martin is years away, and Bentley’s 2026 ‘urban EV’ isn’t striving to be any kind of dynamic benchmark.

The question, then, is why is Ferrari bothering? ‘For two reasons,’ explains CEO Benedetto Vigna. ‘Number one, because we want to show that it is possible to harness any technology to delight our clients. And we do the electric Ferrari because we want to widen as much as possible our client base.’

Vigna’s also keen that Ferrari delivers on its promises, so the EV is coming. It won’t be with us properly until the middle of next year, but we now know a great deal about its concept and technical solutions – the engineering Ferrari hopes will give its EV the kind of margin of superiority its more conventional powertrains almost take for granted.

What do you want to know?

Give it to me straight: it’s not going to be a supercar, is it?

No, it isn’t. Ferrari’s adamant current cell chemistry can’t deliver a big enough performance advantage to offset the weight increase. This isn’t going to be an engine-less 296 GTB or a Ferrari F80 without the V6 – but we already knew that.

Ferrari isn’t ready to confirm the body style, other than to say it’ll have four doors, but we’re expecting a low, cab-forward coupe-SUV not a million miles away from Jaguar’s i-Pace in broad concept. The design is a collaboration between Flavio Manzoni’s team working on the exterior and former Apple designer Jony Ive and LoveFrom – the design collective he founded – working on the interior.

CAR’s vision of the Ferrari EV, illustrated by Andrei Avarvarii

CAR’s vision of the Ferrari EV, illustrated by Andrei Avarvarii

The electric Ferrari uses four electric motors, two on each axle. Total output is north of 1000bhp, with the rear axle alone good for 831bhp. The front axle peaks at 282bhp. Performance, predictably, is shattering: less than 2.5sec 0-62mph and a top speed of 193mph (the same as the Purosangue SUV). Claimed range is more than 330 miles, with maximum charging power of 350kW.

Impressed? Yes? No? That’s the weird thing about electric cars. They long ago blew past even the most powerful of conventional supercars on raw oomph, and machines like the Rimac Nevera and Lotus Evija are so potent the numbers cease to hold any meaning. But Ferrari’s sniffy about dragstrip-blitzing EVs generally, dubbing them ‘elephants’ for their lack of handling finesse.

The electric Ferrari will be a series production car, not a limited-run halo product, and in that sense it’s closer to machines like the forthcoming Cayenne Electric than it is a Rimac. In flagship Turbo guise the Porsche (which uses two e-motors, rather than four, and a 113kWh battery) also puts out more than 1000bhp. At 122kWh the Ferrari has a bigger battery and weighs less. Maranello’s claiming 2300kg, so a good 300kg lighter than the Cayenne Electric Turbo (if 300kg heavier than the V12-engined Purosangue).

Tell me about the motors

Everything about the new e-axles – the technology, the control software and the manufacturing – is being done by Ferrari, in Maranello. Ferrari’s keen to point out that while this might be its first electric production car, this is not its first electrified rodeo. It first met the challenge of F1’s KERS era back in 2009, with the F399, and since then we’ve had the 599 Hy-KERS prototype, a decade of V6 hybrid F1 cars and a string of hybridised road cars, including the LaFerrari, SF90 Stradale, 296 GTB and now the F80.

As well as system total power, Ferrari’s also talking about specific output for its drive units – 4.3bhp per kg at the front and 6.4bhp per kg at the rear. As you might expect, those figures compare favourably with, say, BMW’s latest Gen6 electric powertrains which, while built to very different cost and volume parameters, are also state of the art. BMW’s kit is rated at 120kg and 296bhp for the rear units, so 2.47bhp per kg, and 70kg and 178bhp at the front, or 2.54bhp per kg.

Ferrari’s motors are permanent-magnet units, able to spin to 25,000rpm at the rear and 30,000 at the front, and they’re related to the motor on the F80’s front axle, giving the hardware top-tier performance credentials right out of the gate.

While powerful, Ferrari’s also chuffed with how compact and efficient the units are – a product, it claims, of motorsport learnings, not least the use of Halbach arrays; a unique orientation of the magnets to create a strong, focused magnetic field precisely where Ferrari’s engineers want it. Heat build-up within the tightly packed stator is the enemy of high-performance motors and Ferrari’s battling it not with direct oil cooling of the stator, as Porsche does in the new Cayenne’s high-output rear motor, but with a high thermal conductivity resin (40 times higher than air). It’s vacuum-impregnated into the stator to move heat efficiently out of the motors and into the liquid cooling system.

It’s claimed the resin also boosts mechanical strength – a serious consideration given the centrifugal forces involved. To which end, the motors also feature 1.6mm thick carbon sleeves that press-fit into the rotors and help safeguard the individual magnets from the enormous forces they’re subjected to at peak revs. Thermally stable (whereas metal sleeves would cause issues with heat expansion), the solution helps maintain a stable and very tight – 0.5mm – air gap between the stator and the rotor, boosting efficiency.

Lightweight and compact inverters, packaged with the drive units, manage the switching from DC current to AC and back again under regen (at up to 500kW – the Cayenne can go to 600kW – and 0.68g, to recharge the battery pack). They wield huge control over how the powertrain drives and feels, and Ferrari’s using some smart inverter management to eke out a little more range. Torque is supplied to meet the driver’s requirements by switching rapidly between nothing and twice the torque demand, so the mean torque is as requested but power consumption is reduced, giving another six miles of range in highway use, Ferrari claims.

And the battery? Ferrari’s own kit too?

Yes, kind of. Under the watchful gaze of technically fluent, pro-innovation CEO Vigna, Ferrari’s doing the Elettrica (not its actual name – we must wait for that) the hard way, with no trolley dashes for easy off-the-shelf solutions. Except for the cells themselves. The battery unit has been developed by Ferrari and final assembly takes place at Maranello, but the cells are by Korean firm SK On, with which Ferrari’s collaborated for years on its hybrids.

The battery capacity is one of the biggest we’ve seen on an EV at 122kWh gross (Ferrari is still working to maximise the net figure). Most of it is located under the floor, between the front and rear axles, with the final 15 per cent under the rear seats. The car’s overall weight distribution is 47 per cent front, 53 per cent rear.

As is common practice on performance EVs, the battery forms an integral part of the structure, being firmly bolted into the monocoque at no fewer than 20 anchor points, thereby using its not insignificant weight and rigidity to enhance structural stiffness. As you’d imagine, it also does a lot of good work reducing the car’s centre of gravity – Ferrari reckons it’s 80mm lower than would be the case in an equivalent combustion-engined car.

CAR’s vision of the Ferrari EV, illustrated by Andrei Avarvarii

CAR’s vision of the Ferrari EV, illustrated by Andrei Avarvarii

Removable and repairable, the battery is cooled by three cooling plates – two on the main housing and a third, smaller plate on the section of the battery beneath the rear seats. Where Porsche cools the Cayenne’s 113kWh battery from both sides, Ferrari only cools on the underside, using a cooling system capable of going from a flow rate of 51 litres per minute to 351 litres per minute if you’re really digging into the car’s performance. It claims metal plates within the modules move the heat out of the battery so efficiently there’s no need to cool it from both sides.

So-called cell-to-pack construction, which does away with modules and packs the battery with as many cells as possible, is popular for its increased capacity within a given set of dimensions. But the downside is access. As Ferrari puts it, ‘when a cell dies, the product dies’. Instead, the Elettrica has long life at the heart of its battery philosophy, with Ferrari talking of the units ‘having the same performance forever’. If a cell or module becomes problematic, the battery can be removed and that module – there are 15, each containing 14 pouch-type cells – replaced.

Should I care? It’s not actually going to be fun to drive, is it?

Ferrari says the new car will have more usability than either the now discontinued GTC4 Lusso or the Purosangue, but with the potential for higher driving thrills than both. Indeed, Ferrari has incessantly talked up its EV’s driving dynamics, right from the very top.

‘We develop new technologies out of a desire to improve the quality of life, not only from a utility point of view but also for fun,’ CEO Vigna told CAR in an exclusive interview last year. ‘The electric car will do this. I have driven it, and it is something unique. When you talk about electric cars today, you’re generally talking about something heavy and okay on linear acceleration. But when you go to lateral acceleration, the feeling in the body, the gyroscope in the ears, this is de-coupled and you do not feel well. The people making electric cars today have to optimise the cost – we have the luxury of not having to do this.’

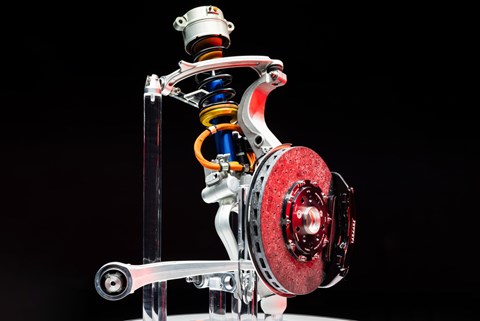

We now know Vigna was referencing the Elettrica’s chassis systems, which make it something of a milestone car. Rear-wheel steering, a version of the Purosangue’s active suspension system and the massive torque vectoring power of the four-motor powertrain make this, in Ferrari’s words, a car capable of fully active cornering, freeing the Elettrica of the compromises that bedevil more conventionally engineered cars.

The active suspension system is an evolution of the Multimatic system with lighter shock absorbers (by 2kg), a 20% longer pitch on the threaded damper shafts, for finer control over vertical movements, and oil temperature sensors for more consistent performance. The system promises to be able to make the Elettrica the quietest, most comfortable and most refined Ferrari yet – and yet every bit as hilariously agile as the Purosangue when you’re on a charge, perhaps even more so.

Using powerful electric motors and threaded shafts on each corner of the car, the system has complete authority over the car’s attitude. With it, there’s no need to compromise between ride quality and body control – you can have both. And together with all-wheel drive, four-wheel steering and powerful torque vectoring, the net result should be an EV that moves on the road like nothing else of a comparable size and weight. Indeed, Ferrari talks of the effect being equivalent to a 450kg weight reduction.

But what of the theatre of a true Ferrari? The spine-tingling noise and the thrill of working up and down the gearbox, either with a ball-topped shift lever in an open gate or with paddles? Well, the Elettrica’s attempting to give you that, too.

The Elettrica features shift paddles and a ‘gearbox’, or at least a set of five pre-determined levels of torque between which you can move via the paddles; left for down, right for up. First Hyundai, then Porsche, soon AMG, now Ferrari – it seems no one serious about developing a driver-focused EV can bring themselves to ignore the idea of an imitation gearbox. And why not? The idea might sound gimmicky, but Hyundai’s Ioniq 5 N proved the reality, well executed, can be very satisfying, making the car both easier and more enjoyable to drive.

And on the noise front, there’ll be some – when you want it. Mostly the Ferrari will assume you’re driving electric because you want some peace and quiet. But make a big input at the throttle or get busy on the shift paddles and the Elettrica will make noise – real noise.

An accelerometer mounted at a specific point on the rear motor casing (they tried 50 locations before getting it right), which vibrates at different frequencies depending on speed and load, will feed this effort and vibration to the cabin as noise, giving, in Ferrari’s words, ‘an authentic voice to the electric motors’. A noise cancellation system will weed out the unpleasant frequencies and bring the nice ones up in the mix. It’s not fake noise. But neither is it pure or analogue like exhaust or inlet noise. Ferrari uses an electric guitar analogy, and it holds. As with an electric guitar, the sound still comes from an authentic source, but the noise is amplified electronically, not by the body of the guitar.

Confused? In part that’s because Ferrari’s undoubtedly holding plenty of information back. But perhaps Antonio Palermo, a manager within Ferrari’s NVH and sound quality team, can explain.

‘We were sure from day one that we didn’t want to just replicate the sound of an internal combustion engine, and we were sure that we didn’t want to invent a new sound. So that was the puzzle. An exhaust pipe conveys sound with pressure waves, right? The air is moving back and forth – a natural sound that easily reaches our ears. How can we extract the sound from our e-axle? We need a sensor, an accelerometer, to pick up the sound trapped in the metal which we can then amplify. This sound is authentic; the components are speaking for themselves, without the need for us to invent anything.

‘With the signal from the accelerometer we have lots of possibilities, and one of these is deciding when we want to hear that sound and when we do not. On a long commute, cruising on a highway, you don’t need that sound. You want a quiet, comfortable car. And that’s what this Ferrari will also be. But let’s say it is a more extreme drive, or you are engaging with the paddles. Now the sound will be amplified, and it will give you information about what you’re doing. If you go from big positive torque to lifting off and regenerating, there will be a small hit in the gears, going from pushing to pulling, and the accelerometer will feel this immediately. We are returning normal feedback to the driver.’

Without disclosing his solution, BMW M division boss Frank van Meel spoke years ago of the need for a system like this, to give the driver the feedback and tactility required to drive at the limit safely.

‘Imagine a wheel that is spinning; you have lost grip,’ continues Palermo. ‘The revs will increase and again, the sensor will pick this up and, via sound, you will know. We call this language and connection.’

Just how authentic is this noise really, given the levels of amplification and editing going on?

‘Yes, we are sculpting the noise,’ continues Palermo. ‘The gear whine is going to be annoying, so there is no point in amplifying that, but there are a lot of beautiful frequencies that we can help flourish. We are speaking all the time about orchestras when we talk about combustion engines, but there is an orchestra inside this car too. And the sound is very clear, very detailed. We find with our test drivers they can tell which wheel is spinning faster, whether it’s on the right or on the left, and the sound is not steady. The timbre oscillates, and this is what connects your brain to what is going on.’

The system works hand in glove with the simulated gearbox, Torque Shift Engagement, and it’s preoccupied Ferrari for years, with much deliberation and handwringing, as Palermo explains. ‘It took us a long time to get a consensus. The first customer for us is our test drivers – they gave us the confidence that we were on the right path. Then, with the test driver as a shield in front of me, I went to upper management. We tested many times, and for us it was really a great chance to involve the whole company, from the operational levels to the higher levels, hearing the comments of people who are coming to the project with a fresh perspective. Yes, there was a lot of debate. But we were agreed: no replica sound, no invented sound.’

There is nowhere to hide with Ferrari’s first EV – the world is watching. But Ferrari’s used to that, needs the attention, feeds off it. In the words of CEO Vigna: ‘One beautiful purpose of our company is to audaciously define the limits of what is possible. If we do not innovate, we are not a market leader.’